The Idea of Justice

Recently, a mentor of mine, a man who brought me into the D&I space reached out to me concerned after I republished an article written by the later Dr. R. Roosevelt Thomas, Jr., who is hailed as “the Father of Diversity Management”

His article “The Shamming of Diversity” was published shortly after he died in 2013. Dr. Thomas also wrote a diversity management book entitled, Beyond Race and Gender in 1991.

He was clear that a persistent and reductionist focus on race and gender à la the civil rights, social justice, and affirmative action paradigms of the 1960-70s were short-sighted and didn’t allow for the transformational potential of diversity management, then diversity and inclusion, and now what most know as DEI to flourish.

Alternatively, he offered two other paradigms that speak to individual strengths and the organizational and related market mixtures (similarities and differences) that were always at play and created the inevitable tension and complexity that needed to be effectively managed to create the conditions for success for all stakeholders. That is the internal and external contributors that could help and/or generate divergence from fulfilling the company mission and purpose.

Dr. Thomas was right in that where we are today in the DEI conversation is one that is based on limited notions of social justice and civil rights. Let me be clear. I am very well-versed in the historical atrocities perpetuated toward minorities across the globe. They have been horrendous and my compassion never wanes.

Conversely, what has transpired from too many so-called practitioners and supporters of DEI over the past decade-plus (and more mainstream beyond academia the past four-plus years), in the name of addressing the atrocities of the past on behalf of the most marginalized has not been done so with a lens for much more than how one feels in response to stimuli.

George Floyd’s death, along with a handful of other televised killings and harm done to other racialized people, has been heavy stimuli. The resultant energy that people believe would solve the problem is rage. Rage at the police. Rage at the “system.” Rage at white people, especially white men.

The rage fests were often carried out online. I am too lazy and disinterested to pull out all of the threads of back and forth, calling out anyone who stepped out of line with the popular discourse about police killing black people more than whites. “If you are not part of the anti-racist cause, you are part of the racist solution.” It was a litany of pent up pain. I sometimes felt it myself during the past few years, and for certain years back.

And, the more I read, I realized that most of those raging through their pain were under-informed about the realities of police killing (vs. harassing and over-indexing on black people). They were underinformed about the (other) systemic causes for so-called black poverty and lack of agency. They were very well-informed about how they felt and their individual lived experiences, framing them as universal and all the fault of the so-called other.

Growing up in Topeka, KS in mostly white neighborhoods and in mixed-race/culture schools, with business-owning, fiscally and culturally conservative parents who were coming of age at the advent of the Civil Rights Era, gave me a perspective that contrasts with a significant amount what I have observed from those pushing an agenda that didn’t seem aimed at progress but at retribution, redistribution, and reparation(s).

Lived Experience + Toxicity

Yes, I get the types of justice that are often talked about. I have studied them, and the more significant influence on my thinking has been that of economist Amartya Sen. His use of the comparison of the Sanskrit words, Niti and Nyaya in particular:

“Drawing on the Sanskrit literature on ethics and jurisprudence, he outlines a distinction between niti and nyaya; both of these terms can be translated as “justice” but they summarise rather different notions (pp. 20 ff). Niti refers to correct procedures, formal rules, and institutions; nyaya is a broader, more inclusive concept that looks to the world that emerges from the institutions we create, rather than focusing directly on the institutions themselves.”

Speaking to the Asian Society of Northern California, Sen addressed the issue of affirmative action in India. He explained that Niti drives the policy, which should be a Nyaya-based approach. He noted that affirmative action can only achieve so much (which I agree with and have written about).

With regard to affirmative action's being extended based on religion, Sen argues that, "Categorization does not have to be based on the basis of religion. It should be based on social deprivation, and for that you need a more sophisticated theory of affirmative action."

He also noted that often religion-based affirmative action policies can have unintended negative consequences for the poor of certain faiths.

"It is a miscarriage of the intention of affirmative action if low-caste, poor Hindus are favored more than Muslims who belong to the corresponding social strata and are often not entitled on grounds of not being a Hindu," he said.

Sen reflects on how the “social” in social justice activism can become much less than. It can become tribal, retributive, and destined for an avalanche of backlash.

Those who equated social justice and anti-racism with DEI in the past several years didn’t consider the tradeoffs. Their righteous pursuit so blinded them that it didn’t matter what the results of their actions produced.

In a way, it was an insatiable pursuit of rightness. And, as you have heard me say before, “Rightness has never transformed anything.”

Now, back to my mentor, to some extent he knows about most of what I share above concerning my stance. And, he was cautioning me to not be so critical of the DEI industry. As he shared his sentiments when we spoke, I found myself in my feelings.

Why were you feeling so heavy, Amri? Was it because he is a white man (who happens to be Jewish, but that doesn’t matter, right)? Was it because I felt lectured at? Was it because I felt that I was right? There is a “yes/maybe” answer to at least one of the above questions.

When I thought deeply, I realized that my heaviness was mainly and ironically because I felt a sense of release. I have been mindfully and lovingly (I believe) critical of how DEI was being positioned as anti-racism and social justice rather than “creating the conditions for people to thrive and organizations to create value–fiscal and societal” (how I, in part, define inclusion).

At the point of his reaching out, I knew, and he reminded me of his love and respect for me. I disagreed with him, but over the past several years, any entry into a social media thread to challenge the standpoints of my social justice/anti-racist advocate colleagues has resulted in condescension, ostracism, and other forms of distancing.

I might even say I have been quiet-canceled by some, as they don’t engage when I comment on their posts. There have been some exceptions, but most either ignore my comments or do the digital equivalent of patting me on the head, and some have unfollowed me.

While this has been disappointing, I get it. As Upton Sinclair says, “It is hard for a man to understand something that his paycheck depends on him not understanding.”

Since my last book was published, I have worked hard to understand and reframe the upside-down targets on the letters DEI. The responses from social justice practitioners have been primarily defensive or dismissive for concern that perceived negative sentiment might sway someone to take it further.

If we can be critical of and honest about our own approaches, we can correct and evolve them. I remain committed to this. This I will continue despite what seems like the industry's crumbling. In reality, it is NOT.

It is a necessary market correction. How it is being done is wrong-headed and not intended to better the United States government or companies. Yet, if you remain committed to the principles of the work of inclusion and diversity, the time has never been better to ride the stress and use it to strengthen the space–to go beyond resilience.

That is, we must install practices and instill principles that leave people at all levels of the organizational hierarchy with greater capacity to create the conditions to thrive through all storms, just like we, as practitioners, must in the current one.

I am not trying to, nor have I ever tried to defend DEI. I have been committed to promoting the wise practice and principles of our work. I have been writing and speaking to bring broader perspectives about what DEI is and is not—sharing it with those willing to be influenced toward a perspective that sees the work beyond the reductionist lens that both pro and anti-DEI people can perpetuate.

That reductionist lens proposes that DEI is all about group identities, the grievances about mistreatment, and hiring these people as a result of their persistent complaints and threats. The anti-DEI people use the small percentage of practitioners who have become popular with this kind of work to represent what DEI is.

(By the way, I am not naive to the fact that there apeople making a living on Boogeymanning (is that a word?) DEI. They are another manifestation of the Sinclair quote above. The anti-DEI “influencers” will ride the wave of the next several months or years, confronting companies on their DEI practices, demanding they stop them (or else. . .ooooh!). These people are challenging companies’ rights to do whatever the Fuddruckers they want to.

If companies are worried about the backlash from the public and the current U.S. administration, I implore you not to succumb to the same reductionist push that in part created the anti-DEI storm (i.e., not pushing back out of fear of being called racist or white supremacist against dumb or wrong-headed approaches that some who styled themselves DEI advocates perpetuated).

Target is in limbo now because they reacted and didn’t gauge the storm's direction. Stop DEI out of demands by a grifter, and he’s got you in his grasp. It won’t matter what you do next.

If you change your direction based on principles, the need for reconsideration, and staying out of the silliness crosshairs, you can move toward creating something durable. You can be the architect of your message to the marketplace versus individuals trying to make a career out of defining your intentions, in a manner that benefits them.

Instead, ask questions. Go on the record as to what these “don’t say DEI” pushes by people being paid to target you, about what you are doing in your firm, are meant to change. For that matter, your board members need to question their understanding, too. Your culture matters, so these conversations cannot be short-sighted like the poorly thought-out DEI approaches of the past few years have been.

I will soon be sharing more about how to approach inclusion in a principle-centered way. And I am always up for a conversation ahead of that.

So, my mentor got me thinking, “Yeah, I have been critical. And if someone like my mentor, who, after nearly forty years, and knows more about this space than most, is willing to be in dialogue with me, I must persist and engage more in threads that I have self-censored and distanced myself from the past 18 months or so.

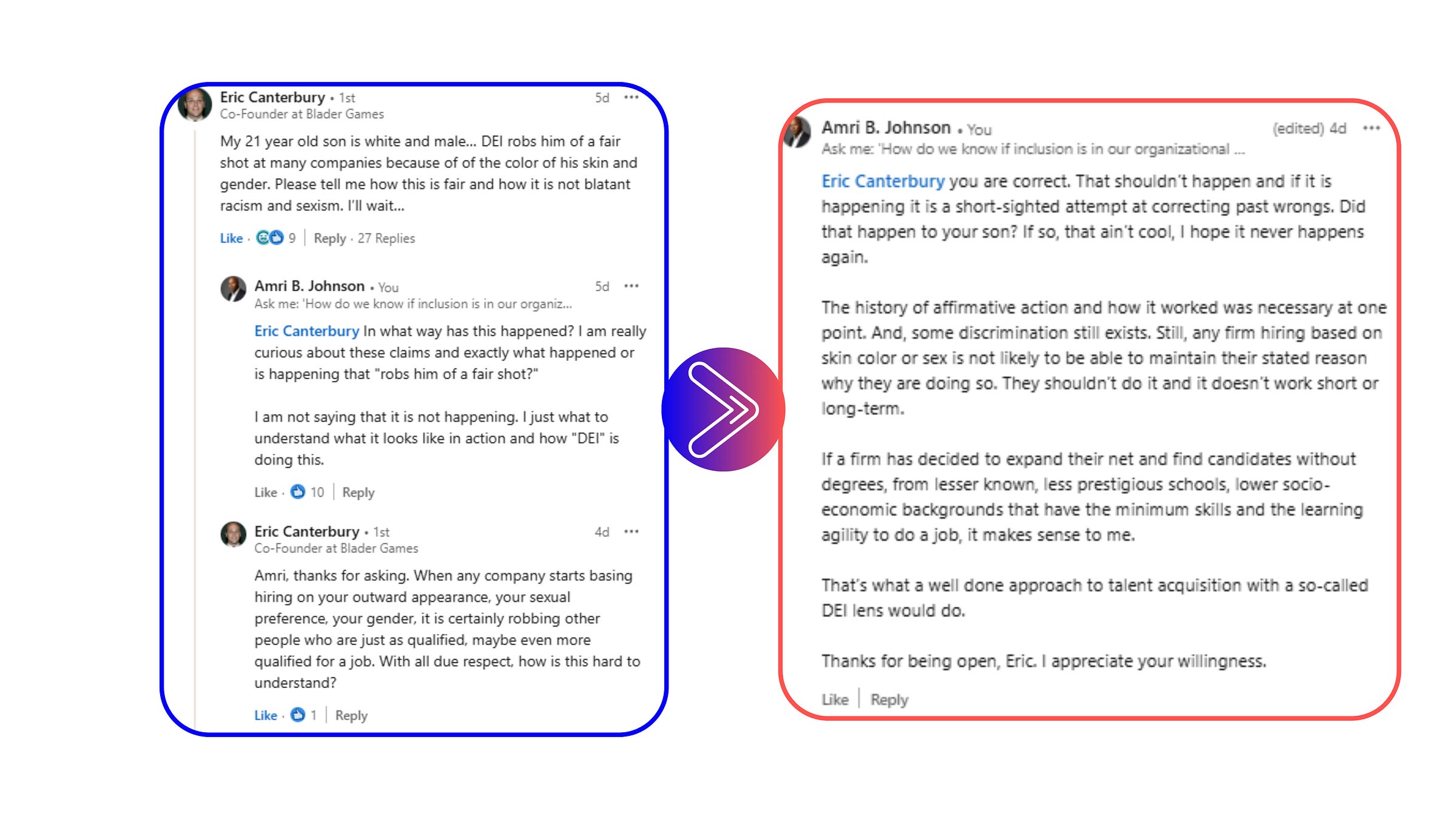

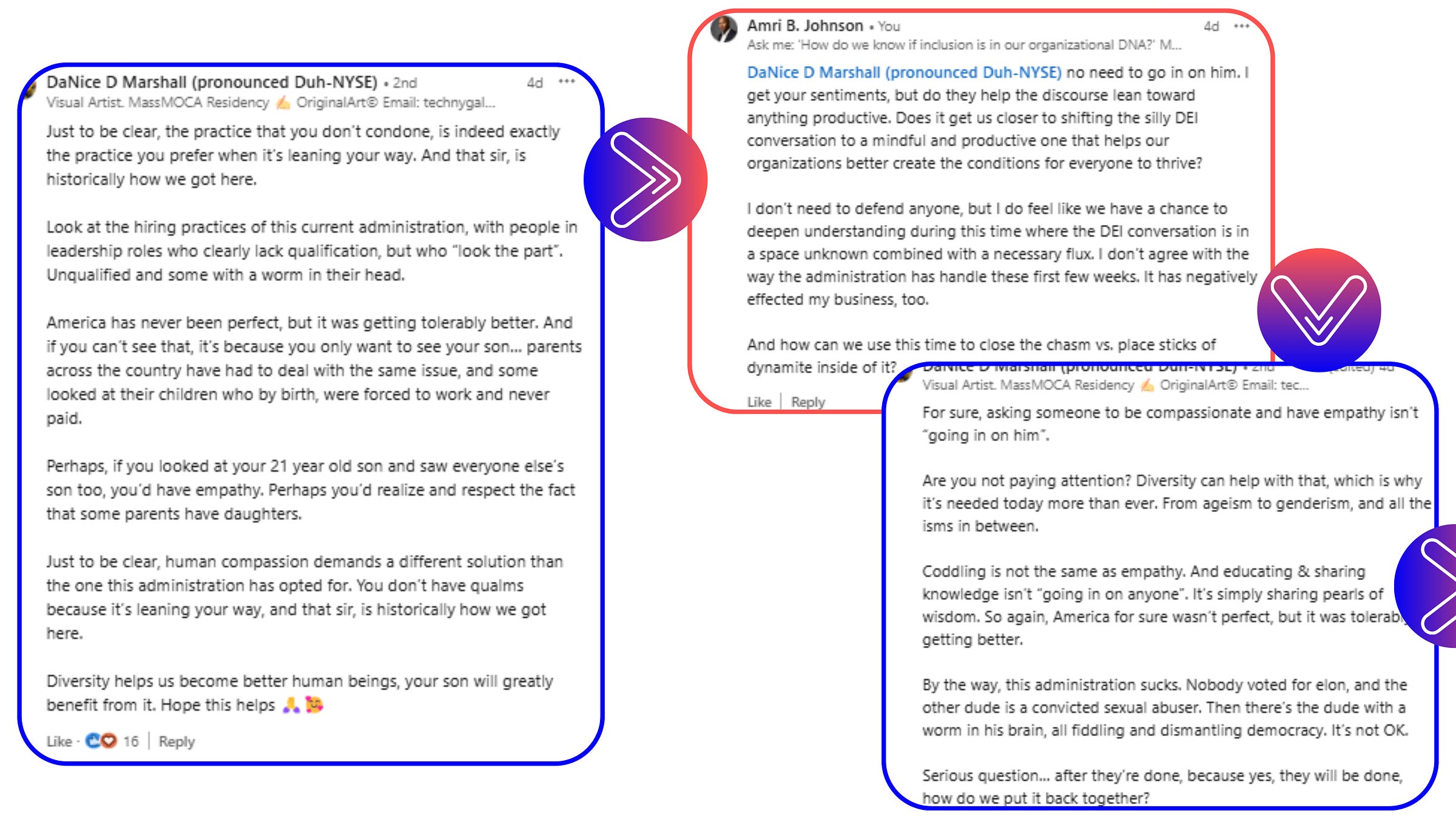

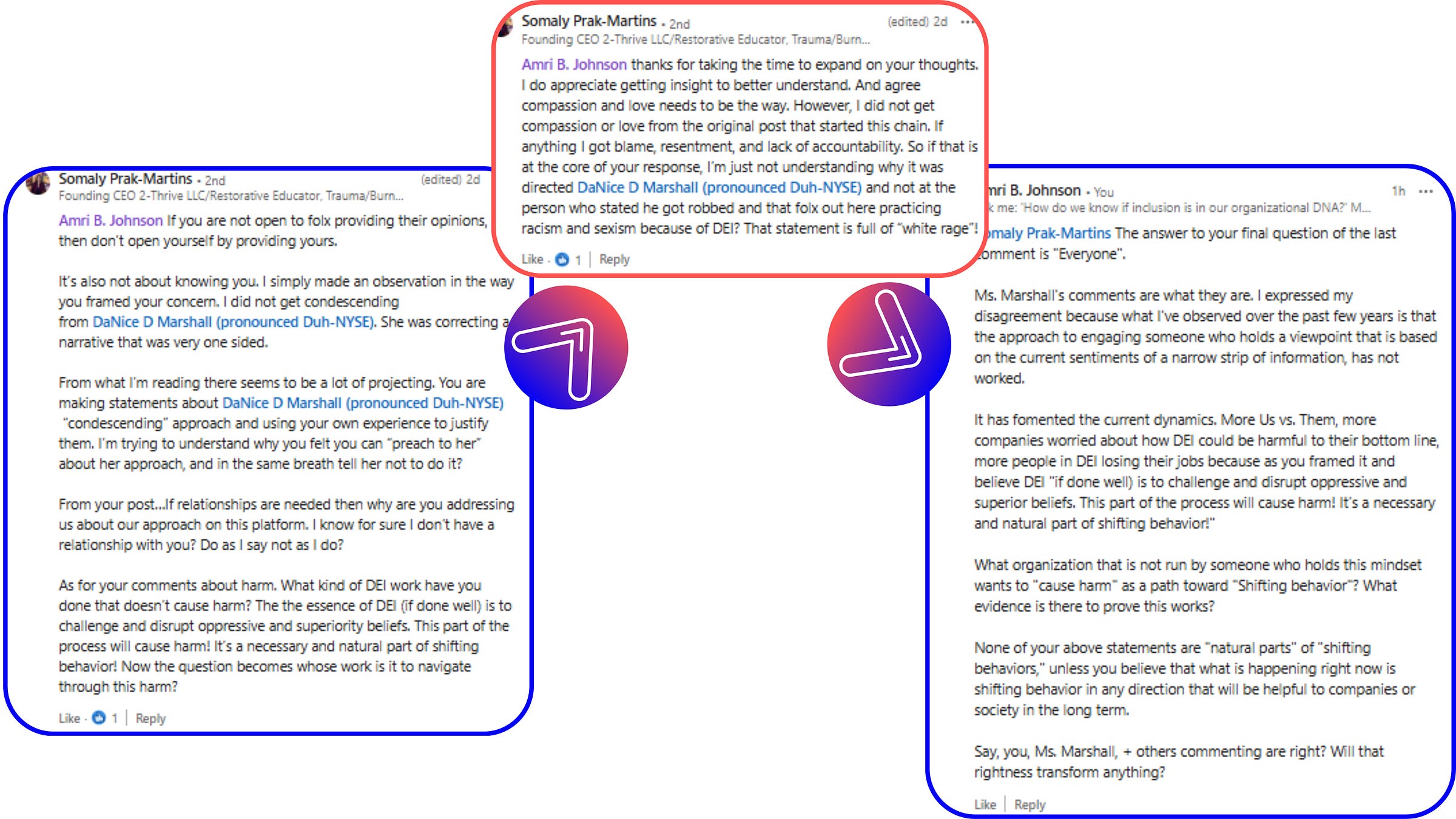

I’ve recently waded into a few threads to engage with people and see what would emerge. Some have not responded like in days of old. In the screenshots below, you can see the results of one of my dives into a thread with potential for contention and tension.

The majority in this particular, none who have done this work at the same depth and scale as me, had an allergic reaction to how I challenged one commenter. That is she pushed back on what I interpreted as an unhelpful (to the work of DEI): “Dear White Man, let me tell you why you are wrong” comment. I figured it would be a bit provocative. The contrary responses were expected. I would have even appreciated this kind of response from anti-racist practitioners in the past. By the way, thanks to the people willing to engage—much appreciated.

I will take what I can get. What do you think of this thread? How can we have more dialogue about what expands the transformational potential of inclusion? That is, far beyond the limitations many social justice and anti-racism efforts have left in their wake.

Ready to transform inclusion from concept to culture?

When inclusion becomes "the way we do things around here," it transforms from initiative to being a key part of organizational identity.

Want to be part of this transformation? Join our free EMERGENT Inclusion Framework virtual event. Whether you're a skeptic or champion, your voice matters in this conversation.

I hope this was helpful. . . Make it a great day! ✌🏿