If Only Advocates and Adversaries of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Could. . .

Since the release of Reconstructing Inclusion two and a half years ago, much of my writing has revolved around a concern—and a hope—if only. . .

That concern persists along with hope today but for different reasons than in 2023.

My current concern is that both advocates and adversaries—the pro-DEI and anti-DEI camps—have framed DEI as at least one of the following. Let's call these:

Twenty Faulty Frames for DEI

It is. . .

The right thing to do.

A very bad, biased, and discriminatory thing to do.

Something that must "DIE".

The best thing for helping "marginalized people" gain equity.

Equality of Outcomes

Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo [books]

Cultural Marxism

Policing of Speech/An attack on freedom of speech

Antiracism

Help for the "Blacks"

Protection of the "The [Illegal] Immigrants"

Support of the "LGBQs" [Lifestyle]

"Trans" [are women/men] [are not XX/XY]

Turning kids trans without their parents' permission or consultation.

Hiring people unqualified for their roles based on visible characteristics.

Hiring people who would otherwise not get a shot due to bias.

Identitarianism

Efforts to eradicate [systemic] racism, sexism, ageism, transphobia, homophobia, ableism, Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism, etc.

Intersectionality

Critical [Race] Theory/Critical Social Justice

The above list is not in a particular order, is not exhaustive, and is perhaps a bit redundant. I intentionally shared a relatively equal number of frames for those who consider themselves for and against DEI.

You will see that many of the points on the list, both those for DEI and against it, overlap. Others, I added [additional context] as such because of the polarized beliefs that are frequently shared.

Since diversity is a mixture of similarities and differences, some of what we see on this list is part of the “diversity” mixture of any human community because personal positions, traditions, and preferences always are. All of the ideas contain biases, yet they are not separate from humanity. [I am not seeking agreement of anyone’s individual preferences, positions, and traditions. My point is that, like these things or not, all ideas in existence are held by humans and thus cannot be separated from humanity.]

Here is the thing: this list is NOT diversity and inclusion. It does NOT create or move organizations closer to practicing equity–at least not in the way I see it. There are things on this list that have been sold as DEI positively and negatively, sometimes both.

Skin in the Game

As you start to agree or disagree with me (likely mostly disagree), consider that most people didn't know what DEI was until the past few years.

How do I know? I know because I didn't start using the three letters regularly until 2021 and still waffle because of the list of faulty frames above.

I have been working in the field of inclusion and diversity since 2003. Perhaps I was under a rock, blinkered by corporate life, and not following trends. This is always possible when you're inside a large company, similar to how it can happen deep inside an academic institution or any other place where a monocultural orientation can cast blinding shadows.

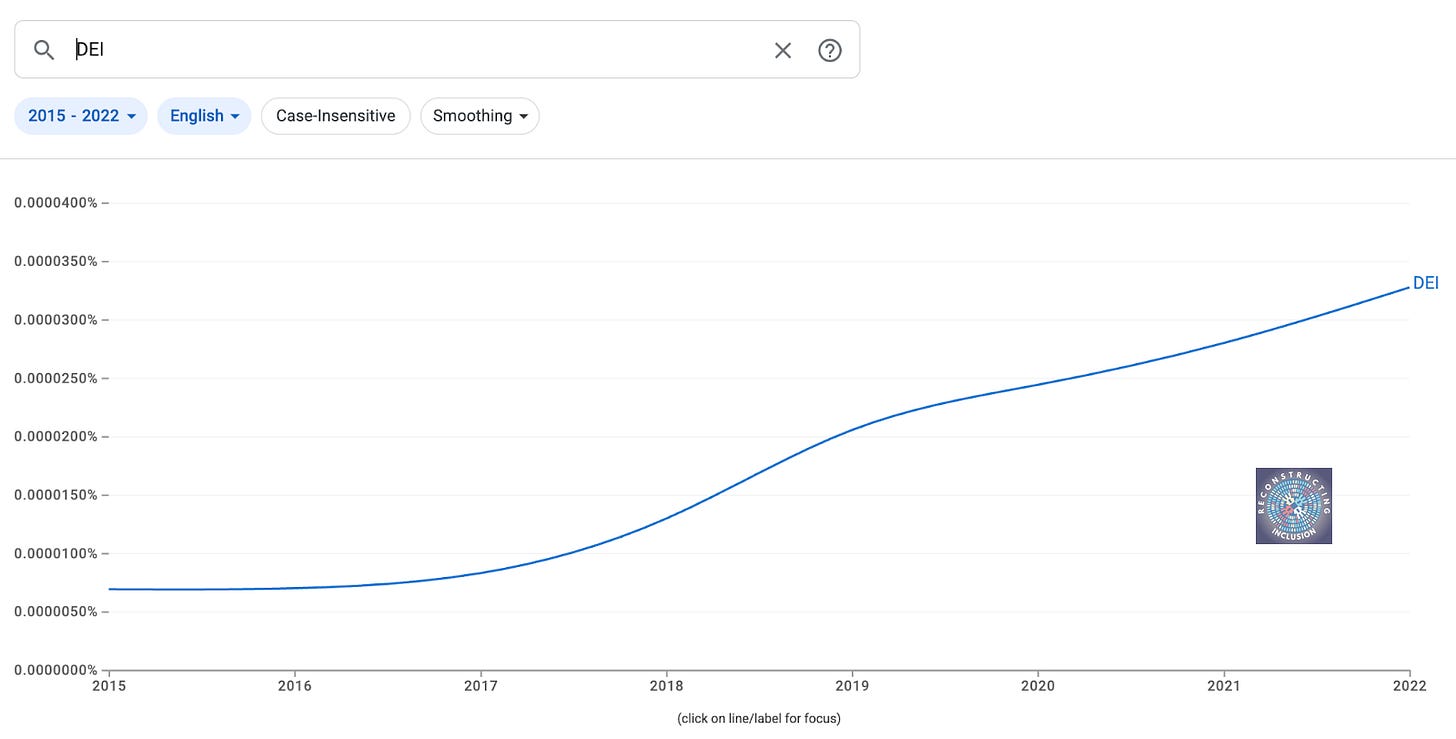

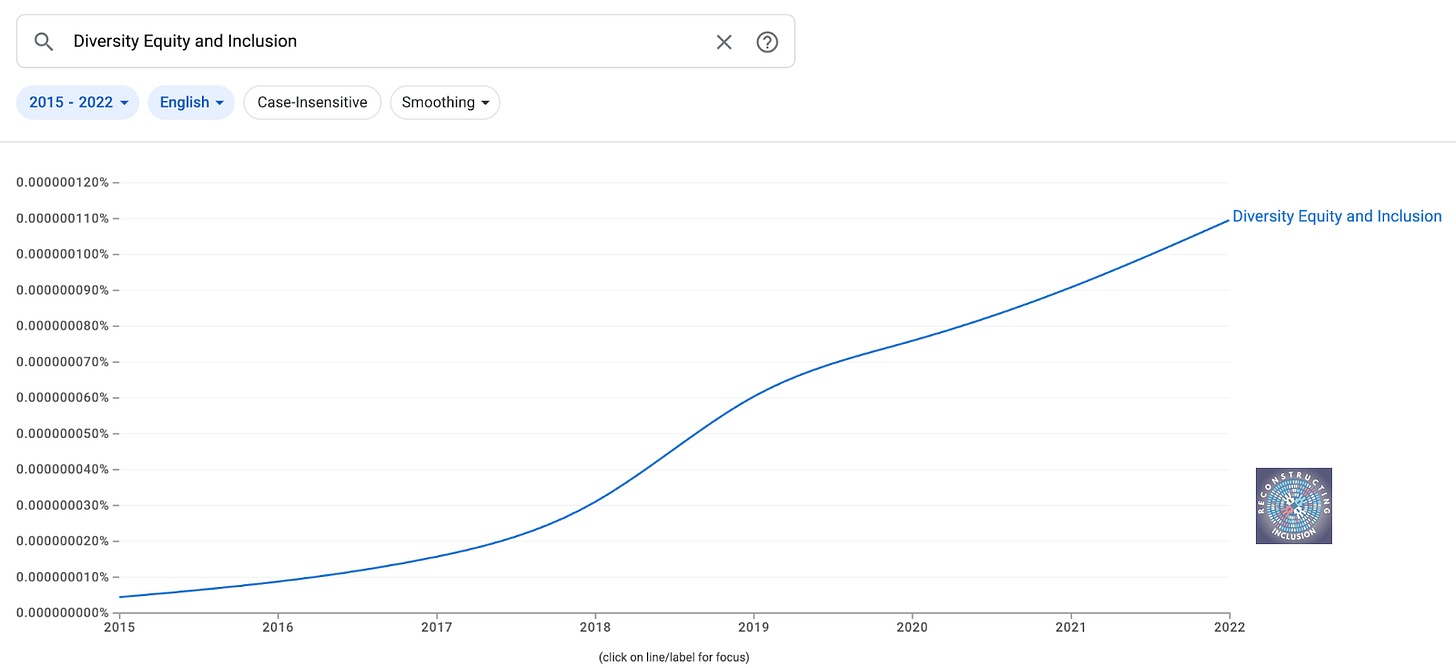

That's why we have Google Ngram Viewer to tell me what I missed. It turns out others were not using the term(s) very much either, at least not in books.

If you are unfamiliar with it, the Google Ngram Viewer is a tool that charts the frequency of words or phrases (n-grams) across a vast corpus of books scanned by Google, primarily from the Google Books project.

Here's what the axes represent:

X-Axis: Time (Years)

The horizontal axis (X) shows the years ranging from 1500 to 2024 (data availability for my search could only go to 2022 as the 2024 data set has only recently been uploaded).

Y-Axis: Frequency (%)

The vertical axis (Y) shows the relative frequency of the term as a percentage of all words published in a given year.

This means that frequency (%) = (number of times the term appears in books that year) / (total number of words in all books that year).

I entered the terms "DEI" and "Diversity Equity and Inclusion." From 2015 to 2022, the usage in books increased by 302% for 'DEI' and, respectively, 2444% for 'Diversity Equity and Inclusion.'

The previous seven years yielded a significantly lower frequency of word usage. For "Diversity Equity and Inclusion", there were no mentions in books until 2011, and then a 71% increase until 2014. For "DEI", a decrease of 32%.

I am not sure if DEI when spelled as Dei shows up in the counts before 2011 because of religious terms such as Opus Dei, the Work of God (which has had its own controversy), or Dei verbum (Word of God), and simply Dei (God in Latin).

I imagine if the spiritual connotation (not a dogmatic religious one, to be clear [for the atheists]) was at the heart of the work we call DEI, the contention we are seeing would be less pronounced. Perhaps.

Obviously, compared to other words used across all books in the Google Books project, these terms are not in the top 10%. Maybe not top 90%

And I can guarantee that the words will have shown tremendous increases when the data becomes available for 2023-25. Why?

Well, one, because the heightened period between the pandemic, George Floyd's death, and the current zeitgeist has amalgamated into a lava-like red zone attracting heat-seeking missiles for all that is wrong about the world and the so-called "other" as it pertains to the elements of the above list of twenty faulty frames that people have for DEI.

That means the good, bad, and ugly of the letters 'D, E, and I' have been used not to light the way for human communities to shape their futures together but rather have, in too many cases, created the opposite effect, despite some (not all) good (righteous) intentions.

Next, let me go further because many of my colleagues in the diversity and inclusion industry are sensitive to criticism (as are anti-DEI folks, but this is just for my practitioner colleagues unless one is willing to see how pro and anti are in a similar boat of wanting DEI to persist, but for different reasons).

It is a challenging period for people's businesses, myself included, and internal practitioners (within organizations). So, hearing anything that sounds like it could cause greater adversity, even from one experiencing similar hardship, and it could be hard to digest.

Thus, let me be clear about what I mean.

There are good-faith actors who believe in the principles of diversity and inclusion, like Monica Harris, for example. Monica is a serious and well-informed critic of DEI, as are her colleagues and advisors at Fair For All.

Many of their advisors, like Eli Steele, have criticized DEI/Diversity/Affirmative Action policies for decades (along with his father, Shelby, whom I greatly respect and have been reading since college.)

And there are people who are in the game for fame. Or, they found fame, and that became their game. Many of the purveyors of racialized narratives of doom are among those. I am not one to call people out by name.

It is not my aim to make others wrong. I often say that "rightness has never transformed anything." However, I do mention a couple of them in the list of twenty DEI framings above. At the pole of anti-DEI, I have discussed other examples (not exhaustively because there are many on both sides of the silly anti/pro-DEI dichotomy) in previous pieces.

I mention Monica and Eli, who have been consistent in their stances against DEI (in many ways that I frame in the twenty above) and clear regarding their reasons. I can add others like Greg Lukianoff, who has also been critical of DEI on college campuses.

After reading Greg's book The Coddling of the American Mind with Jonathan Haidt in 2019 and subsequently watching a debate between him and a well-known and well-resourced academic and popular DEI influencer, and even hosting a screening of The Coddling Movie I became clearer that the principles of free speech he has spent his career defending are, in my view, clearly in line with how inclusion is practiced with an everyone agenda.

That is, inclusion skills and capabilities allow people to grow through robust engagement, respect, and relatedness. Engagement that creates space for many viewpoints, visions, and values is missing from many conversations about what inclusion is and can do.

In fact, it is rare that someone who is passionate about something like free speech engages in an earnest (optimally face-to-face) conversation with a passionate antiracism practitioner, if it happens at all.

Why might that be?

My hypothesis is that many impassioned free-speech advocates are not entirely for free speech. They advocate for speech that suits them to be free. Many antiracism practitioners are such because of how racialization has defined their worldview. There aren’t many guiderails in either—it’s a feeling thing, not a principled one.

Conversely, a few highly principled adherents of free speech defend it, even when they disagree with what is being said. Greg Lukianoff is a rare free speech adherent who acts on first principles of free speech and believes in it even when he disagrees with the content of the speech.

That doesn't mean FIRE protects hate speech or that which connotes harassment or likely acts of violence. It does mean that they stand up for principles that protect against violations of the First Amendment, even during political maelstroms.

This suggests that if someone says something offensive to me or to another, I don't have to like it. It can make me feel angry, sad, or even scared. It can still be said.

For those who take a principle-centered approach to DEI (or inclusion and the tensions and complexity of similarities and differences, where my focus lies), you are open to engaging with those who are making their mark as being known as anti-DEI.

In this case, there is a willingness. At least, there is one on my part.

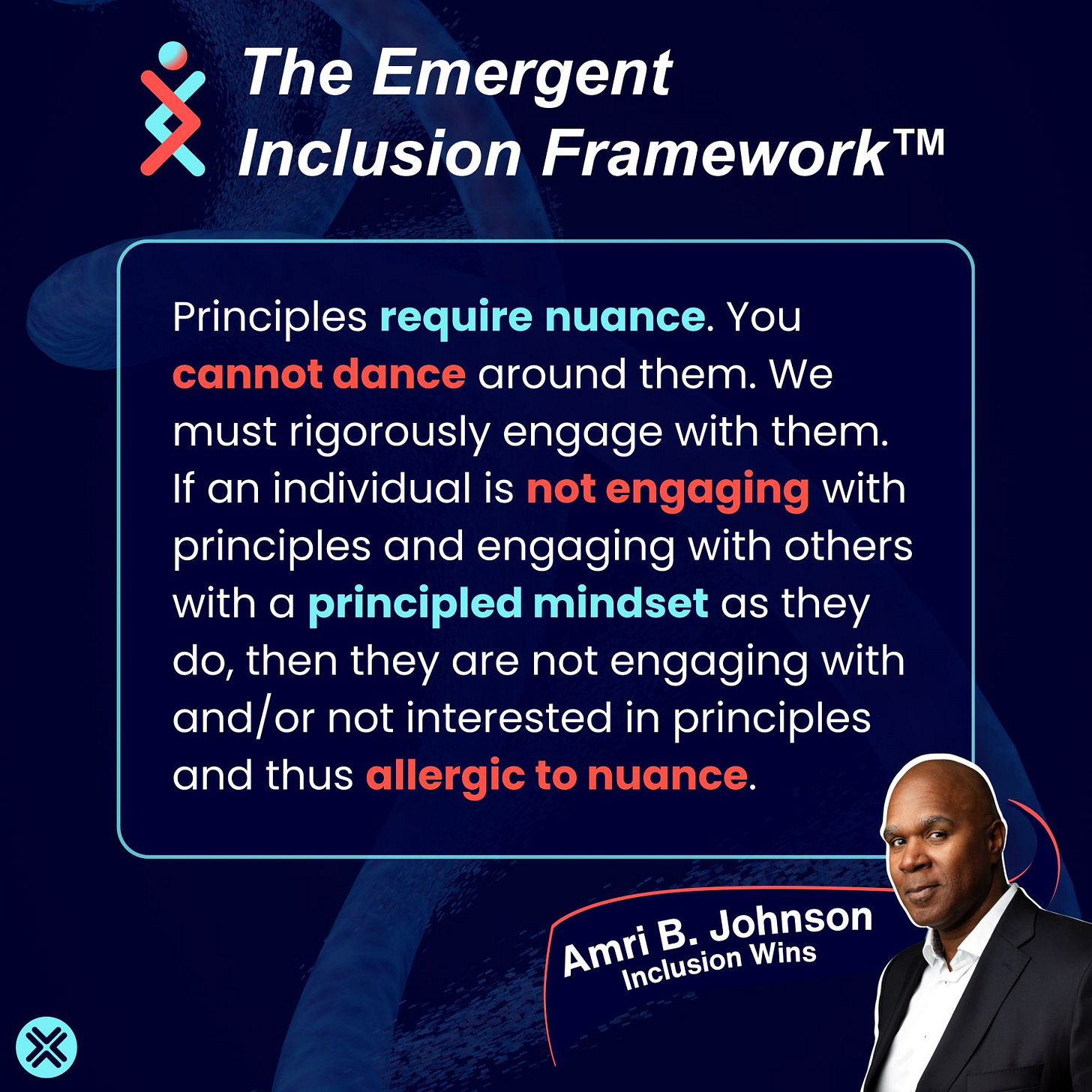

A practitioner of DEI or someone who works in the people and organizational development industry from a set of first principles (they exist, by the way) like agency, dignity, access to opportunity, social responsibility and personal contribution to human communities, and systems-thinking (particularly interdependence) would be ready and willing to have any attachment to the twenty faulty frames challenged.

In fact, if any of their framings are questioned, they will check it with their principles. They may not be willing to completely let it go, but they are likely to ask themselves if its sustainability can be adhered to.

I went through this process with race and racialization.

For many years, I have been clear that race is a trope after reading Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr.'s statement, "Race has become a trope of ultimate, irreducible difference between cultures, linguistic groups, or adherents of specific belief systems which, more often than not, also have fundamentally opposed economic interests."

I came across this quote in 2009, right around the time I was making my first (and likely my last) transition into the corporate world (as an employee) at age 38.

I got to know Dr. Gates loosely while living in Cambridge (USA). We shared the same barber, as did many other prominent Harvard professors, including my Morehouse College brother, Ronald Sullivan, Jr., one of the top constitutional scholars in the world, and the Jesse Climenko Clinical Professor of Law at Harvard Law School.

Beyond watching documentaries and reading some of Dr. Gates' work and knowing his reputation for being one of the coolest professors one could know, I didn't know what to think of this "trope" language.

After meeting and listening to Skip, I understood that he was steeped in the so-called "Black" tradition culturally.

Strongly influenced by Albert Murray, Professor Gates illustrated, at least to me in our brief exchanges, that the emphasis on race beyond historical acknowledgment and necessity was a fiction with no clear biological basis.

This was before the Human Genome Project, which proved beyond any scientific doubt that we are 99.9% biologically the same.

Gates agreed with Murray's quote in The Omni Americans:

"The United States is incontestably mulatto. And not just because of its racial mixture, but because of its cultural heritage. To talk about a 'pure' American is to talk pure nonsense."

Gates embodied this rejection of racial purity and celebrated cultural blending as fundamental to American identity. His show, "Finding Your Roots," continues to reveal the mulatto nature of who we are in America and beyond.

After many years, I have come to a similar conclusion that the pursuit of equity, as I define it–

vigilantly ensuring that people in organizations are given what they need to thrive, whether that is procedurally fair conditions, needed access to contribute and, when necessary, compete for opportunities, and the right feedback at the right time to course correct and improve–

is a worthwhile pursuit for humanity independent of racial or other group categorization. And, when the procedural conditions are not followed, mechanisms to vigilantly address the breakdowns are necessary.

My position is that if organizations can reasonably agree that such an approach includes everyone, we all can win (not equally, but sustainably). It is not a zero-sum equation.

I was wrong about race and racialization for a long time. Yet, once I decided that it would not be core to my practice based on what I'd learned, read, and continue to go deeper on–even into the idea of race abolitionism, the complete dismantling of race—the decision held.

From a financial perspective as an independent consultant, the timing for adhering to my principles of not centering race post-Floyd was inconvenient—something I've thought a lot about. Many of those thoughts were had while looking at my P&L statements and balance sheet 😉.

Although I worked with organizations that were focused on racism, in my consultation with them, I’ve openly centered humanity (the superset) while reminding them of the full spectrum of similarities and differences (the supersets) in practice.

Now, some people who consider themselves DEI experts or practitioners and others who are anti-DEI activists may be wedded to one or more of the twenty faulty DEI frames.

If one of the ideas is so deeply embedded in their rhetoric, identity, or brand, they may feel that admitting it needs serious (or even minor) reconsideration could compromise their livelihood.

As Upton Sinclair said: "It's hard for a man to understand something when his salary depends on him not understanding it."

It would take a great deal of courage and a deeper level of integrity to assert that their mental map is not the territory. Thus, admitting one of the frames is faulty requires letting go of rightness, which many are either scared to do or don't feel is worth it. I get it.

If only advocates and adversaries of DEI could look deep into a metaphorical mirror, they'd see a translucent reflection–and, without doubt, they would see the so-called other.

Don’t believe me? Do a thought experiment. Choose one of the faulty frames and then list five reasons to support it and five reasons against it.

Share your lists with me if you don’t see at least one reason on each pro/con list that you agree with. Even better, share your lists with colleagues about your reasons and have them do the same. What do you see?

Want to go further? Ask people in your circles (e.g., personal, professional, organizational) to write lists of what DEI means to them. Do one yourself as well. Compare and contrast. What do you see?

If only. . .

Ready to transform inclusion from concept to action to being a cultural superpower?

When inclusion becomes "the way we do things around here," it transforms from initiative to being a key part of organizational identity.

Want to be part of this transformation? Join our free Emergent Inclusion Framework virtual event. Whether you're a skeptic or champion, your voice matters in this conversation.

I hope to see you there! Tell a friend 😊

I hope this was helpful. . . Make it a great day! ✌🏿