Complex, Adaptive, Emergent, Inclusive Systems

In my first career as an epidemiologist, I was required to think about systems and their relationships.

Thus, thinking about organizations as systems made sense long before I started working in organizational development, inclusion, and culture space.

For example, I used to investigate local outbreaks of communicable diseases. One day, back in the mid-1990s, my colleagues and I were called to investigate a foodborne outbreak.

It turned out that people who got hepatitis A from a popular restaurant ingested red-skinned potato salad. [Note: It is almost always about the potato salad or another mayonnaise-laden breeding ground for viruses or bacteria. And I did investigate one outbreak in South Georgia (USA) where barbequed beef tips were the culprit.🤔 ]

Several factors were involved in the hepatitis outbreak. It is essential to address them all as distinct parts but not without considering their effect on one another and the whole system (i.e., their interdependence).

1) Protect the Public’s Health: This meant informing people who contracted the virus by ingesting the pathogen. Some knew because they developed symptoms. Others may have been vaccinated and didn’t experience the symptoms. Others may have remained asymptomatic but still could be shedding the virus and needed to be tested and made aware of the risks.

Simultaneously, after identifying the vector of the food source and notifying potential cases, we needed to apply sanitary measures to prevent it from affecting other people immediately.

2) Protect the Financial Well-being of the Community: The chef/owner of the restaurant where the outbreak originated owned several restaurants in the city and employed 100s of people. If his brand's reputation were damaged, it would not only be him being affected; his employees, suppliers, and other vendors he did business with for almost two decades would be at risk, too.

3) Protect the People Involved: The “public’s health” includes everyone who ate at or might eat at the affected restaurant. The restaurant staff also required protection.

Hepatitis A is commonly transmitted via feces. We all are likely to ingest feces, whether it is from small insects or in undetectable amounts from other humans.

That reminds me of a story. When I was in college with aspirations to be an epidemiologist, I interned at the Centers for Disease Control. We had to take a few courses that summer, one of which was an introduction to biostatistics and epidemiological methods.

Reconstructing DEI to make it more Accessible, Actionable, and Sustainable?

It was taught by a gentleman named Virgil Peavey. Mr. Peavey is a CDC legend. He trained thousands of public health professionals worldwide for over three decades. His contributions and commitment to public health and people inspired generations to this day, so much so that his legacy lives on in the form of the J. Virgil Peavey Memorial Award.

One day, after lunch, about ten (10) interns, including me, were listening to Virgil walk through a case about a Hepatitis A outbreak. I didn’t know much about hepatitis at age 20, but I was interested in the story.

He described the situation, and then he got to the point where he revealed that the people who got sick did so by ingesting feces. Upon hearing it, the entire class of 20 and 21-year-olds simultaneously cried out, “Ewwwwww!!!”

Virgil paused for a second, looked at us quizzically, and said with his deep southern accent, “Well hell. . .Everything’s got feces in it!”

He then began to talk about it being in various foods and coming from different life forms, from cows to insects. He sounded like Bubba from the movie Forest Gump talking about all the ways shrimp could be prepared.

His thesis of ubiquitous feces was etched in our minds forever. I apologize if it has in yours, too. In any case, whether we deny or accept it, it is true.

Perhaps, Virgil's example gave us a glimpse at the complexity in his example of how poop travels for me to make my point about protecting the people involved, namely the restaurant staff.

The owner/head chef of the restaurant was gay. Many people who worked for him were gay. When cases were interviewed, some people wondered how hepatitis was transmitted and by whom, often with subtle hints about having a sexual transmission hypothesis in their heads.

We were obligated to let those who indicated they held that hypothesis and the majority who didn’t share their conclusion know that index cases could have contracted the disease in many ways. We shared with everyone the risk factors for contracting Hepatitis A, which included travel to certain parts of the world and working in settings where transmission from animal to human or human to human creates a higher probability of infection.

We educated people to go beyond their limited knowledge, mainly with the questions we asked of the contacts. While we may not have shifted them from their underdeveloped thinking, we introduced several other potential ways to look at the phenomena–a more robust dataset/mental model for consideration.

Outbreaks are complex. The people, places, and times that must be determined each have layers. Each person and place has layers of context to contemplate. Each time period has various factors to consider, from primary disease transmission to incubation in a vector, like potato salad and more.

Likewise, organizations are complex adaptive systems (CAS). I have considered this as I have honed my approach to inclusion in organizations over the past twenty-plus years. That means that the core of my approach is about infusing and then embodying inclusion skills that align with what is needed to shape the emergent future embedded in every organizational culture–also known as “the way we do things around here.”

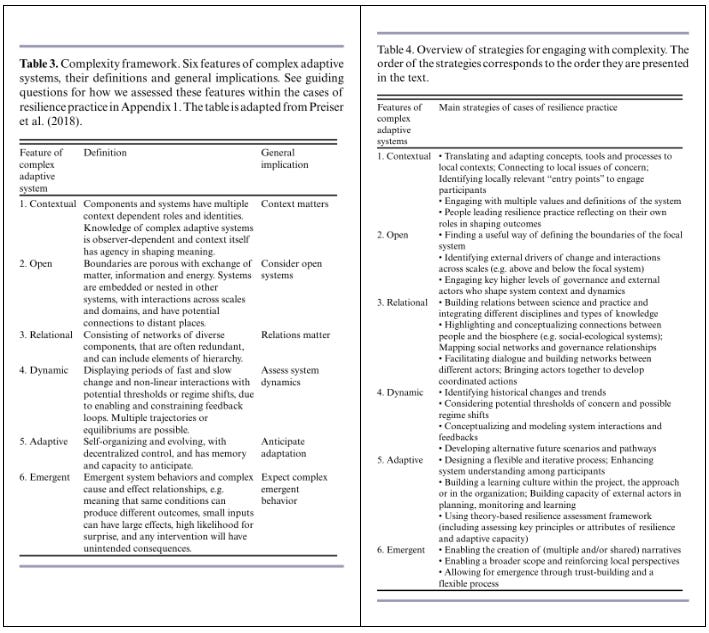

What are the features of a CAS? Sellberg and colleagues pull from the work of Presier et. al., who synthesized the work of many complex adaptive systems scholars and thus describing them via six salient features “to identify activities and strategies used in the cases to deal with the real-world complexity of social-ecological systems, we used a framework of six general features of complex adaptive systems (Preiser et al. 2018). The six features are: 1) contextual, 2) open, 3) relational, 4) dynamic, 5) adaptive, and 6) emergent.”

Tables three and four, adapted from Presier’s work, illustrate a systems complexity framework and strategies for engaging with complexity, respectively. Of course, my description above and the tables are not complete. Myriad people who work in complexity science can expound on this much more eloquently than I do. I am happy to share their names.

As it relates to inclusion and dealing with the tension and complexity of similarities and differences, that’s where my work distinguishes itself and is likely to serve you and your organization differently.

Table three (3) definitions above are either adjacent to or mirror components of my Emergent Inclusion Framework™. I have written and spoken about these elements, skills, and capabilities in this Substack, in my book Reconstructing Inclusion, and in various ways via our podcast.

Below is an example of the thinking that you will find in how we teach The Emergent Inclusion Framework™ for people committed to moving beyond dated DEI practices toward a more accessible, actionable, and aligned way of engagement. One that creates the conditions for everyone in your organization and all stakeholders you serve to thrive.

I mentioned complexity scientists, practitioners, and philosophers above. I have learned from many, including the people of Dave Snowden’s The Cynefin Company. In one workshop I attended, they introduced the participants who were unfamiliar, including me, to Max Boisot (1943-2011). Boisot was a prolific scholar and left a legacy of scholarship and pragmatism in practice that few will ever match in any field.

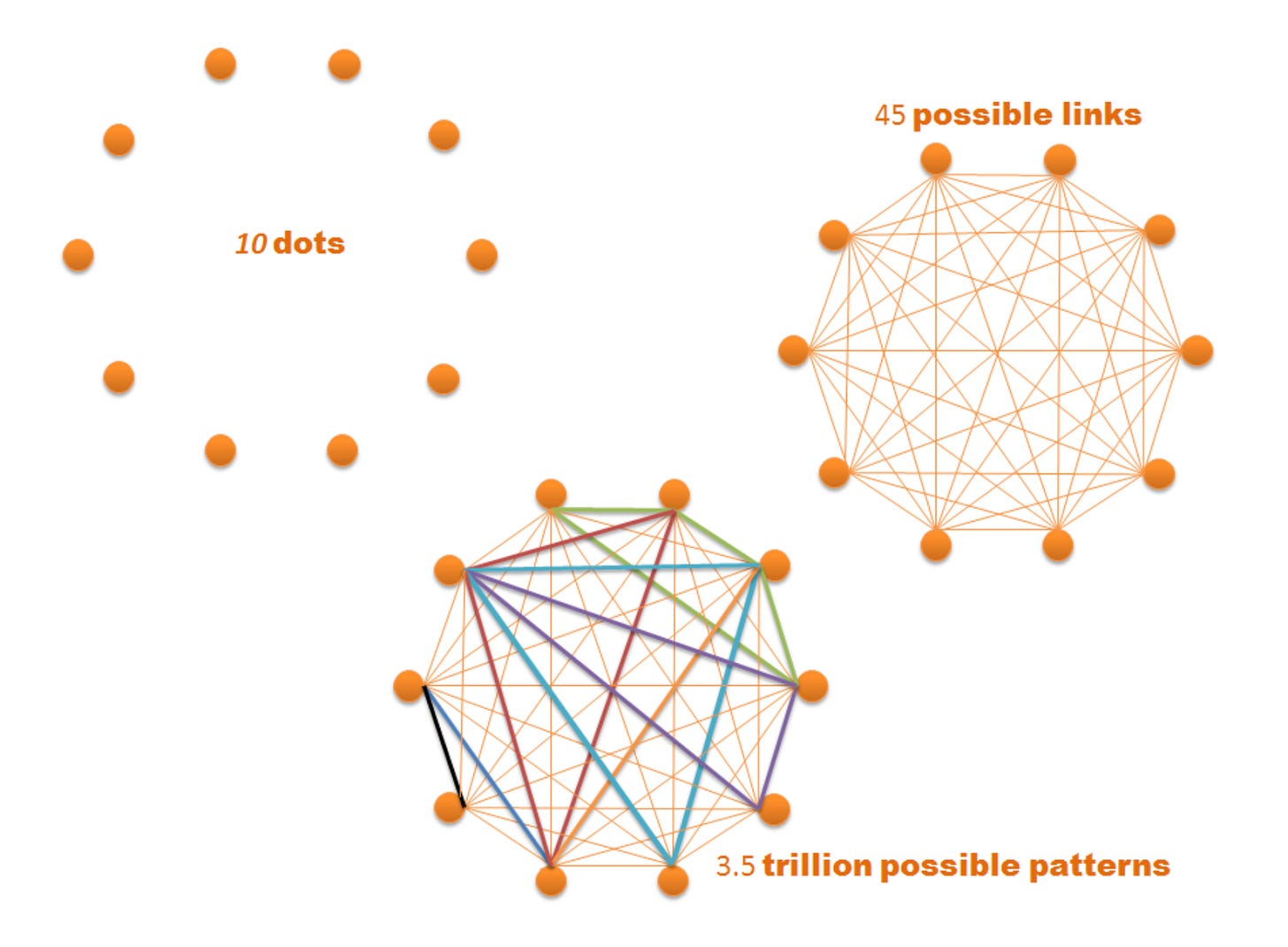

The Cynefin team cited a formula Boisot used to illustrate how different dots, representing a person, place, or thing, along with their various combinations and interactions, produce a variety of patterns that increase exponentially by adding a small number of dots.

The illustrations below visually illustrate the phenomenon. The formula is as follows:

L= N(N–1)/2 | P=2L (L=Number of Lines; N=Number of Dots; P=Number of Patterns).

So, if N=4, we have L=4(3)/2=6 and P=2⁶=64.

Now, this is only if we count each dot as one entity. When it comes to complexity, when it comes to social identity, diversity (i.e., any mixture of similarities and differences and their respective tensions and complexities), a single dot and all it represents will never be a single variable or dimension. With each dot, there is complexity and expanse that changes, at times, from moment to moment.

In other words, the 2D dots you see are more like 4D tesseracts represented by dots that create more patterns and possibilities than we can discern without the reflexive capacity to shift and expand how we sense and respond.

The images below reinforce how more dots (even in the flattened 2D sense) lead to patterns that are impossible to explore in total.

And, if you are thinking that AI could figure out those patterns, think again. Most of these patterns are not recorded in any database. Most are embodied by the interdependent many who possess them. They are exformation.

They can be codified and recorded for future use or dataset training through dialogic learning. Further, if context constantly shifts, no amount of AI in an LLM, SLM, or other machine learning spaces can implement the emergent insights that reside in their users.

Image credit: Sensing Ontologies

Machines cannot make sense of the world or the complexity of organizational life for the collective and connected patterns of 4D dots. Only the 4D dots (the human ones and, in some cases, the non-sentient ones) can do so with one another.

That said, if inclusion skills are not normative in a firm, the sense-making, decision-making, and action-taking processes that drive what an organization sees (information, knowledge, and insight), is (systems), does (systems in action), then the day-to-day seeing, being, and doing remain uncoupled. If such decoupling persists, your capacity to produce consistently solid outcomes via your deliberate and emergent strategy becomes more limited each day.

Join us on April 8th for our Elevating Your Inclusion Edge free interactive virtual event.

We will discuss concepts adjacent to the above and how inclusion is needed more than ever in today’s ever-shifting climate. In the session, I will discuss the necessity of transcending dated paradigms attached to DEI that have reached an impasse and the direction to move in now–how to skate to where the inclusion and culture puck will be.

In our hour together, I expound on our approach–a pathway leading individuals and organizations to create the conditions for people and organizations to thrive consistently.

I hope to see you there! Tell a friend 😊.

I hope this was helpful. . . Make it a great day! ✌🏿